Who Are We Really Fighting? The West? China? or the Markets Between Them

THE PATTERN BEGINS

It started quietly. In the middle of October 2025, MP Materials began to soften after climbing toward an extraordinary high of around a hundred dollars a share. Nothing in its published numbers justified that price, but nothing justified what came next either. As MP began to fall, it dragged an entire sector with it—Australia Lynas, UK’s Pensana, USA Rare Earths and American Resources from the United States—companies that together represent a large proportion of the West’s attempt to build an independent rare-earth supply chain separate from Chinas monopoly.

In less than three weeks the group lost roughly half its market value. It wasn’t project failure or falling demand; it was the behaviour of markets that now react faster than they think. Watching it happen, felt like observing an automated reaction that no longer knew what it was reacting to.

THE SETUP

Through late September and early October 2025, trading volumes across the sector were unusually high. That was understandable. It came against the backdrop of escalating tension between the United States and China, where rare earths had again become part of the language of economic warfare. Beijing was signalling that it could weaponise its dominance in critical minerals. The rest of the world—particularly the United States—had to demonstrate it could respond.

That mixture of anxiety and opportunity drew investors in, pushing liquidity in rare-earth stocks to its highest levels in years. MP Materials, the largest Western producer with the highest market capitalisation, naturally sat in the crosshairs.

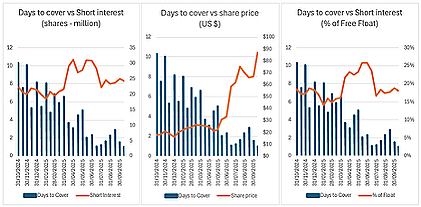

Short interest in MP had been elevated for months—reaching as high 34% of the free float in June 2025—but that extreme level itself didn’t create the selling pressure. At that time, the stock was trading around fifty dollars and the days-to-cover ratio stood at roughly eleven. It would have taken almost two weeks of average volume just to unwind the existing positions. With liquidity that tight, adding to shorts was hazardous: any sustained rally could have left funds unable to buy back shares fast enough to close their positions leaving them exposed to same situation they were exploiting. The scale of the short exposure showed conviction, but it also represented constraint.

What changed was liquidity. As MP edged toward a hundred dollars and trading volumes surged, the days-to-cover ratio collapsed to almost one. Suddenly, the equation flipped. The risk of being trapped disappeared, and with valuations now difficult to defend, the opportunity became irresistible.

By mid-October 2025, nearly eighteen percent of the stock was sold short—well down from Junes 34% but still unusually heavy position for a company of its size. On the following days, more than half of all trades were short sales. Once the first cracks appeared, capital rushed in to widen them.

BEYOND POLICY CONTROL — WHEN MACHINES RUN THE MARKET

Modern equity markets now operate with a level of automation that leaves policymakers reacting to outcomes rather than shaping them. Research by JP Morgan (2017) and the European Securities and Markets Authority (2023) shows that algorithmic and passive strategies account for most of the global trading activity, leaving less than ten percent to traditional discretionary investors.

These systems respond to movement, not motive. As the Bank for International Settlements (2020) observed, automated trading amplifies short-term volatility by reacting to order flow and correlations rather than fundamentals. The subsequent integration of artificial intelligence has intensified this reflex. The BIS (2024) noted that machine-learning models capable of analysing multiple markets simultaneously can reinforce one another when responding to similar signals, accelerating both rallies and declines.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Most investors outside the UK rarely encounter the mechanics of the London Stock Exchange (LSE), yet those mechanics shape how its company’s trade.

The LSE operates two main electronic systems: SETS, a continuous order book for liquid securities, and SETSqx, a hybrid model for smaller or less-liquid shares that relies on market-maker quotes and four daily auctions. Although both are LSE-domiciled, they connect through global liquidity networks with similar platforms, linking London’s trading flow to exchanges in New York, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, and Singapore. The result is a market, policymakers nominally oversee but no longer have any control—a self-sustaining ecosystem where liquidity, volatility, and sentiment circulate at machine speed.

Algorithmic and AI-based trading now form the reflexes of modern finance—efficient, fast, and largely self-referential. Market behaviour increasingly reflects the logic of code rather than the direction of policy. Decisions made in central banks or ministries move more slowly than the algorithms interpreting them.

THE SLIDE

Once MP began to slip, the machines took over. Large funds now rely on models that react to movement, not motive. They don’t ask why something is falling; they see that it is and search for connected names to trade the same way.

Within days the pattern spread through Lynas, Pensana, USA Rare Earths and to a lesser extent, AREC. Each market followed the next as the trading day moved from New York to Sydney to London.

Figure 2:Lynas, Pensana and AREC moved in lockstep with MP Materials. The sell-off spread globally across time-zones, driven not by fundamentals but by algorithms chasing correlation.

Fundamentals hadn’t changed; the correlation was mechanical. By the third week the decline was feeding on itself. Selling created more selling. For smaller companies like Pensana and USA Rare Earths, whose prices had never reflected even a fraction of their long-term value, the damage was wildly out of proportion

HOW THE SYSTEM AMPLIFIED IT

The rare-earth sell-off offered a clear demonstration of how that system behaves in practice. The link between these companies wasn’t geological; it was digital. All five traded on exchanges visible to the same network of U.S. investors and algorithmic funds. MP and AREC sat on NYSE and NASDAQ; Lynas on the ASX but tracked heavily by U.S. ETFs; Pensana on London’s SETS order book and cross-quoted on the U.S. OTC; USA Rare Earths on the OTCQX.

Every tick and order from these platforms feeds the same data engines. When MP fell, the others lit up on the same screens. Companies

like Mkango and Rainbow, however, trade on SETSqx—a slower, quote-driven system with periodic auctions rather than continuous matching. Their prices update less frequently and don’t feed directly into global trading models.

It wasn’t a question of quality; it was one of exposure. If your stock sits inside that global feedback loop, you move with it whether you deserve to or not.

This structural distinction became critical during the rare-earths sell-off. Pensana, which trades on SETS, appeared continuously in global trading models and was swept into the automated reaction that followed the fall in MP Materials. Mkango (MKA) and Rainbow Rare Earths (RBW), listed on SETSqx, were largely shielded. Their auction-based pricing refreshed too slowly to trigger the same algorithmic responses. The difference was not one of quality or fundamentals—it was structural exposure.

THE BOTTOM

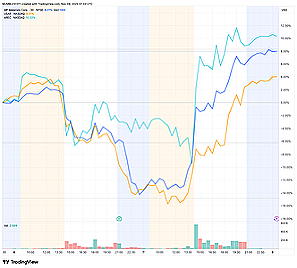

On 6 November MP announced its quarterly results. The figures were solid—strong cash, no unpleasant surprises—but headline-scanning algorithms saw “earnings miss” and sold immediately. The share price dropped six percent within minutes. Then human investors read the report. The picture was fine. Within hours the stock had reversed course, finishing the session roughly twelve percent higher after the close as short sellers scrambled to cover.

The next day, 7 November, the reversal spread across the U.S. market. USA Rare Earths and AREC followed MP’s rebound almost point for point, climbing as the same shorts unwound their positions. That move happened after the London and Sydney markets had closed, which is why Pensana and Lynas didn’t move at the same time—their shares simply couldn’t trade. But for the US traded stocks. It was a textbook bottom—weeks of pressure released in a few hours of forced buying

Figure 3:After MP’s earnings release on 6 November, headline-scanning bots sold first, humans read later. Shorts were forced to cover, sending the whole group sharply higher — the mechanical rebound that marked the floor.

WHAT IT SHOWED

Parts of the sector had overheated, MP Materials most of all. Its valuation had become detached from its published numbers, with Lynas not far behind. But most of the sector, especially the developers, hadn’t yet reflected their underlying fundamentals.

This wasn’t a cleansing correction; it was a mechanical swing that shifted cash, NOT VALUE—mainly from private and retail investors to the trading desks that profit from volatility. MP and Lynas finished the episode still expensive. Everyone else finished it badly bruised and disillusioned.

It demonstrated how easily conviction investors can be flushed out under the appearance of “price discovery.” If this is what passes for efficiency, it’s hard to argue that it serves the industries governments claim to consider strategic.

TWO STEPS FORWARD, ONE STEP BACK

The pattern keeps repeating. Policy moves forward, Capital steps back. Governments announce critical-minerals strategies, alliances and funding frameworks, and within weeks the same markets tear down the companies those policies were meant to lift.

We talk about supply-chain security but trade as if volatility were the goal. The system rewards speed, not staying power. It celebrates risk management on paper but manufactures risk in practice. Each cycle drains confidence and leaves genuine investors more cautious.

IT IS IRONIC THAT THE RARE EARTHS IS SECTOR IS HAVING TO SPEND AS MUCH TIME SURVIVING ITS OWN CAPITAL MARKETS AS DEVELOPING ITS PROJECTS.

FIGHTING OURSELVES AS WELL AS CHINA

China’s advantage began as geological. The world’s largest rare-earth deposit—at Bayan Obo in Inner Mongolia—was first mined for iron. The rare-earth minerals lay literally in the waste. What other countries overlooked, China turned into an industry. By the late 1970s Beijing understood that those tailings contained the materials that would power future technologies: magnets, catalysts, electronics. It invested in processing plants, trained metallurgists and built a supply chain from the ground up.

Geology was the starting point, but policy turned it into power. China combined abundant resources with decades of coordinated planning. It accepted the environmental costs, subsidised processing capacity and pulled every stage of the value chain inside its borders until dependency itself became a strategic weapon.

The West, by contrast, treated geology as an export business, not a strategic asset. Open markets and short-term finance encouraged extraction over development. We mined, we shipped and we told ourselves that processing and manufacturing would happen elsewhere. That mindset still lingers. Even when governments intervene through the MSP, the IRA or EXIM financing, they’re pushing against markets wired for quarterly profit, not long-term security.

China uses capital as an instrument of state policy. The West treats it like sport. We celebrate policy announcements on Monday and short the beneficiaries by Thursday. It isn’t only a contest with China; it’s a contest with ourselves. China wins through unity of purpose. We lose through the absence of it.