WHEN SUPPLY NO LONGER MEETS DEMAND

For much of the past decade, the global rare earths market has operated under a set of assumptions that increasingly no longer hold. Chief among them was the belief that China, as the dominant producer and processor of rare earth materials, would continue to act as a global swing supplier—expanding production as required to stabilise prices and absorb incremental demand from the rest of the world. That assumption underpinned low prices, discouraged investment outside China, and shaped policy responses across the West.

Yet the mechanics that sustained this model were never cost-free. Price stability was achieved not through market balance, but through sustained supply expansion, enforced quotas, and the absorption of global demand into China’s own production system. As long as external demand remained modest relative to China’s domestic requirements, this approach suppressed prices without materially distorting internal cost structures.

That balance appears to be changing. Demand for magnet rare earths continues to grow at mid-single-digit rates, driven by electrification, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing. At the same time, China’s own downstream industries have expanded rapidly, increasing domestic consumption of strategic materials. The combination has placed growing pressure on the very mechanism that previously stabilised global prices.

This paper explores whether recent shifts in Chinese policy—reduced transparency around production quotas, tighter export controls, and an increased emphasis on domestic demand—may reflect an economic recalibration rather than a geopolitical strategy. It considers one plausible interpretation: that China is becoming less willing or able to subsidise global price stability when external demand risks inflating internal costs.

If that interpretation is even partially correct, the implications are significant. Once China ceases to balance global supply and demand, the rest of the world must rediscover a market-clearing price—one that reflects constrained supply, long lead times, and rising capital requirements. In that environment, higher prices are not a policy choice, but an economic necessity, and investment outside China becomes not just viable, but essential.

When Concentration Becomes the Market

Markets do not possess intent, bias, or memory. They are simply the aggregation of inputs — supply availability, cost, timing, and demand — and the prices that emerge from their interaction. In that sense, THE MARKET IS THE MARKET. It does not misbehave, distort, or signal incorrectly. It clears exactly as it must, given the structure it operates within.

In the case of rare earths, that structure has, for more than a decade, been one of extreme concentration. When a single jurisdiction controls approximately 60% of primary supply and close to 90% of processing capacity, price formation no longer reflects the interaction of a dispersed global supply base. It reflects the internal economics of the dominant system.

At that level of concentration, there is no meaningful external marginal supply. There is no swing producer outside the system capable of responding to price signals, no spare processing capacity through which demand can be independently cleared, and no alternative pathway through which scarcity can express itself. The rest of the world cannot influence price formation because it cannot alter the inputs. It can only observe the outputs.

Under these conditions, prices do not fail to reflect demand. They reflect the dominant system’s ability and willingness to supply incremental volumes. If marginal supply can be expanded within that system at acceptable internal cost, additional demand — whether domestic or external — is absorbed through volume rather than price. Stability is not imposed; it emerges naturally from the structure.

This is why price behaviour over the past decade should not be interpreted as distortion, suppression, or mispricing. Prices behaved exactly as they should have, given the inputs. China did not need to influence the market. By virtue of its position in the supply chain, it WAS the market.

Only when those inputs change — through rising internal demand, increasing marginal costs, environmental constraints, or a recalibration of policy priorities — do price outcomes change. The market itself does not change. It remains what it has always been: the logical output of the structure within which it operates.

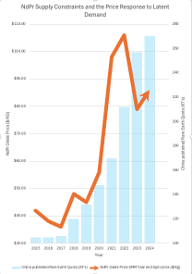

Evidence of Supply Expansion: A Decade of Rising Chinese Quotas

This mechanism is visible in the trajectory of Chinese rare earth production quotas over the past decade. Mining and separation quotas rose steadily, often at rates sufficient to absorb both domestic consumption growth and incremental demand from the rest of the world.

The effect of these increases was cumulative. Rather than responding episodically to price spikes, quota expansion acted as a persistent buffer against scarcity. Each increase reinforced the expectation that supply would continue to arrive as needed, anchoring price expectations and limiting the incentive for alternative supply development elsewhere.

The important point is not the precise annual figures, but the direction and persistence of growth. Quotas functioned as a stabilising tool, allowing China to absorb demand shocks internally and export price stability externally.

Flat Prices in a Growing Market

The effectiveness of this strategy is evident in price behaviour. Over the same period that quotas expanded, prices for magnet rare earths such as NdPr remained largely range-bound, punctuated by brief spikes but lacking sustained upward momentum.

This price behaviour is difficult to reconcile with demand fundamentals alone. End-use demand expanded steadily, yet prices failed to respond in a manner consistent with tightening supply. The most plausible explanation was that supply expansion dominated price formation.

The reality was that rising demand was repeatedly met with rising supply, preventing the emergence of sustained scarcity. As a result, price signals that might otherwise have triggered investment outside China were suppressed.

Notes to Chart: Chinese rare earth production quotas expanded steadily between 2015 and 2024, absorbing both domestic and external demand. In 2023, the issuance of three quota rounds rather than the usual two coincided with a sharp deceleration in demand growth following the COVID period, resulting in a pronounced price correction. Despite this temporary dislocation, the broader pattern illustrates how sustained supply expansion dominated price formation over the period.

Why the Old Model Became Unsustainable

The stabilising mechanism described above depended on one critical condition: that marginal supply could continue to be expanded without imposing unacceptable costs elsewhere in the system. Over time, that condition weakened

China’s own domestic demand for rare earths increased sharply as downstream industries—electric vehicles, wind turbines, robotics, electronics, and defence manufacturing—expanded. At the same time, environmental enforcement tightened, illegal mining was curtailed, and marginal ore quality declined. Each additional tonne became more expensive to produce.

In this context, supplying external buyers at scale began to exert upward pressure on internal cost structures. What had previously stabilised global prices increasingly risked destabilising domestic ones. Continuing to expand supply to subsidise global price stability became progressively less attractive.

A Possible Interpretation of China’s Current Policy Direction

Against this backdrop, recent policy developments warrant consideration. Transparency around production quotas has diminished, export licensing has tightened, and official policy increasingly emphasises domestic consumption and industrial self-sufficiency.

One plausible interpretation is that China is recalibrating its role in the global rare earth market. Rather than acting as a global swing supplier, it may now be prioritising the balance of domestic supply and demand. In such a framework, export availability becomes residual, and price outcomes outside China become less central to policy objectives.

This interpretation does not require assumptions of strategic intent or geopolitical hostility. It is consistent with a more consumption-led economic model in which strategic inputs are managed primarily to support internal industry.

Bifurcation and the Emerging Divergence in Pricing

While bifurcated pricing is often discussed as a theoretical outcome, there is growing evidence that such a divergence is already emerging in practice. Prices paid for rare earth materials outside China increasingly differ from reference prices observed within the Chinese domestic market.

A particularly clear illustration is provided by the arrangements agreed between MP Materials and the U.S. Department of Defence. These included not only a price floor mechanism designed to ensure the economic viability of non-Chinese production, but also direct government participation through an equity stake. Importantly, this structure was not imposed unilaterally by the producer; it reflects institutional recognition that prevailing spot prices—largely anchored to Chinese domestic references—were insufficient to sustain secure supply outside China on a purely commercial basis.

The significance of this intervention lies less in its specific terms than in what it acknowledges. Both price support and capital participation were required to bridge the gap between domestic Chinese pricing and the price necessary to support production, processing, and reinvestment elsewhere. In effect, the arrangement formalises acceptance of a higher clearing price for non-Chinese supply and recognises that this price may not be discoverable through spot markets alone.

Additional anecdotal evidence reinforces this divergence. OEMs and magnet manufacturers operating outside China increasingly report paying prices materially above those published by Chinese price reporting agencies such as SMM. These transactions are typically private, long-term, and structured around security of supply rather than spot optimisation. As a result, they are rarely reflected in public benchmarks, which continue to reference conditions within the Chinese domestic market.

This divergence reflects fundamental differences in market structure. Chinese domestic prices remain influenced by internal policy priorities, managed supply, and local cost considerations. Prices paid in the rest of the world increasingly incorporate risk premia related to jurisdiction, regulatory compliance, financing costs, and the strategic value of assured supply.

Taken together, these developments suggest that bifurcation is no longer merely a prospective outcome, but an emerging market reality. The rest of the world is already paying prices that reflect scarcity and risk, even where public benchmarks continue to suggest otherwise. That sustaining non-Chinese supply has required both price support and equity participation underscores how far market-clearing prices outside China have already diverged from domestic Chinese references.

When Demand Growth Exceeds Supply Growth

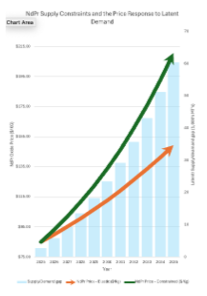

Demand for magnet rare earths is widely forecast to grow at mid-single-digit rates, commonly around 5–6% per annum. On its own, such growth would not normally imply dramatic price appreciation.

Prices, however, are not set by average demand growth. They are set at the margin—by the gap between realised supply and required supply at any given point in time. When supply growth is constrained, delayed, or mis-timed, even modest demand growth can produce outsized price responses.

The distinction between demand CAGR and effective supply growth is therefore critical. Where supply fails to keep pace in practice, prices must rise until new investment becomes viable.

What Constrained Supply Implies for Prices: Applying Adamas

This distinction is reflected in forward-looking analyses such as those produced by Adamas Intelligence. While demand growth assumptions remain broadly consistent with mid-single-digit forecasts, price outcomes diverge sharply once supply constraints are incorporated.

Applied to a starting price of approximately $85,000 per tonne, a smooth planning curve might imply price growth of around 5–6% per annum. In contrast, Adamas’ constrained-supply outlook implies a materially steeper trajectory, closer to low-double-digit annual growth over the medium term.

These two curves do not represent disagreement about demand. They represent different assumptions about supply elasticity. When supply can expand freely, prices track demand. When it cannot, prices reprice to restore incentives.

Assuming a broadly balanced NdPr market at the end of 2024, differing demand and supply growth rates imply a widening latent supply–demand gap over the medium term. While realised volumes always clear, prices are set at the margin. Under constrained supply conditions, the price required to induce new capacity rises materially above the path implied by elastic supply assumptions.

Implications for the Rest of the World

If China increasingly balances only its own supply and demand requirements, the rest of the world must clear the market without access to China’s marginal volumes. In a sector characterised by long lead times, limited spare capacity, and capital constraints, that process exerts upward pressure on prices.

Higher prices, in this context, are not a sign of market failure. They are the mechanism by which investment outside China becomes economic. What was previously uneconomic under a regime of price suppression becomes viable once the swing supplier steps back.

CONCLUSION

PRICING AFTER THE SWING SUPPLIER

For over a decade, global rare earth pricing was anchored by a single assumption: that China would continue to expand supply to stabilise markets and suppress volatility. That assumption shaped investment behaviour, policy decisions, and perceptions of risk across the rest of the world. It also ensured that most supply expansion outside China remained uneconomic.

The evidence presented here suggests that this model has reached its limits. Sustained quota expansion successfully absorbed global demand and held prices in check, but at the cost of increasing pressure on China’s own domestic supply–demand balance. As internal consumption has grown, the economic rationale for continuing to subsidise global price stability has weakened.

One plausible interpretation of recent policy developments is that China is now prioritising domestic market balance over global price anchoring. Reduced transparency, export licensing, and a greater tolerance for price divergence between internal and external markets are all consistent with such a shift. This need not imply hostility or strategic weaponisation; it may simply reflect the realities of a more consumption-led economic model.

The consequence, however, is unavoidable. If China balances only its own supply and demand requirements, the rest of the world must clear the market without the benefit of China’s marginal volumes. In a sector characterised by long lead times, limited spare capacity, and capital constraints, that process exerts upward pressure on prices until new supply becomes economic.

If the analysis set out in this paper is correct, it has important implications for how risk in the rare earth sector is assessed. Much of the perceived investment risk over the past decade was a function of price outcomes anchored to a market structure in which marginal supply was consistently available from a single dominant system. As that structure changes, price formation changes with it.

In such a context, risks that were previously viewed as structural — persistently low prices, limited price responsiveness to demand growth, and an inability to clear new supply — may need to be reconsidered. This does not eliminate execution, financing, or technical risk, but it does suggest that the price risk embedded in many investment assumptions may no longer reflect the market that is now emerging. A recalibration of risk, rather than a change in market fundamentals, may therefore be required.

In this context, higher rare earth prices should not be viewed as a market failure, but as a signal that a long-suppressed investment cycle is finally re-emerging. Expansion of supply outside China is no longer a speculative hedge against geopolitical risk; it is a rational economic response to structural change. Once China prices for itself, the rest of the world must price for scarcity—and act accordingly.