Thoughts on resources, human capital, power and investment

(And some other stuff……)

Latest Blogs

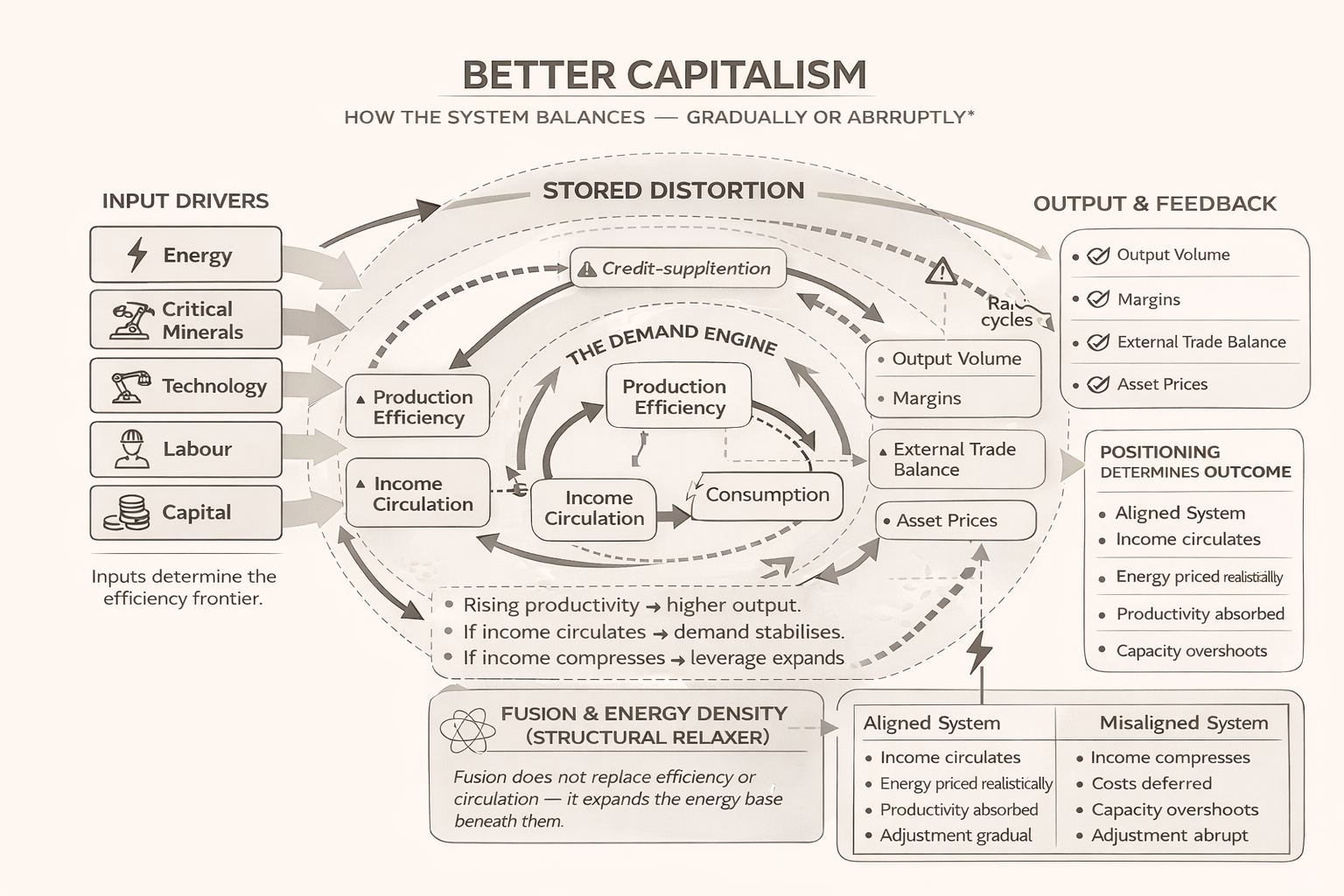

This paper begins with a simple observation: markets balance, but not always gently. Distortions in leverage, energy pricing, resource use, or income distribution can persist for years before adjustment occurs. When it does, it is rarely neutral.

Automation and electrification are reshaping production. Electricity is becoming the dominant form of usable energy across transport, manufacturing, robotics, and digital infrastructure. Critical minerals — small in monetary value but central in function — determine how efficiently that shift can proceed. Rare earths sit at key technical choke points. The possibility of fusion raises the question of whether the energy base itself could change.

Efficiency alone does not ensure stability. Margin depends on volume, and volume depends on broad and solvent demand. If gains concentrate faster than they circulate, leverage fills the gap. If costs are deferred, constraint eventually returns.

Markets will clear. The question is whether balance arrives gradually — or through correction.

Advanced economies are entering a phase of electrification driven not only by decarbonisation, but by efficiency and productivity. Electricity converts energy into work more effectively than combustion, and rising demand from electrified transport, heating and artificial intelligence is reshaping power systems. Meeting this demand requires sustained, long-term investment in generation and grid infrastructure.

At the same time, windfall taxation and price caps have re-emerged as politically attractive responses to periods of elevated profitability or tight supply in energy markets. This essay examines the tension between short electoral cycles and multi-decade infrastructure investment horizons. It argues that retrospective intervention alters capital expectations and raises required returns — with consequences already visible in energy markets.

The central issue is not the fairness of taxation, but the alignment of political time with capital time in an economy increasingly dependent on long-lived physical infrastructure. When recovery periods shorten and required returns rise, amortisation mathematics translates directly into higher electricity costs for households and industry.

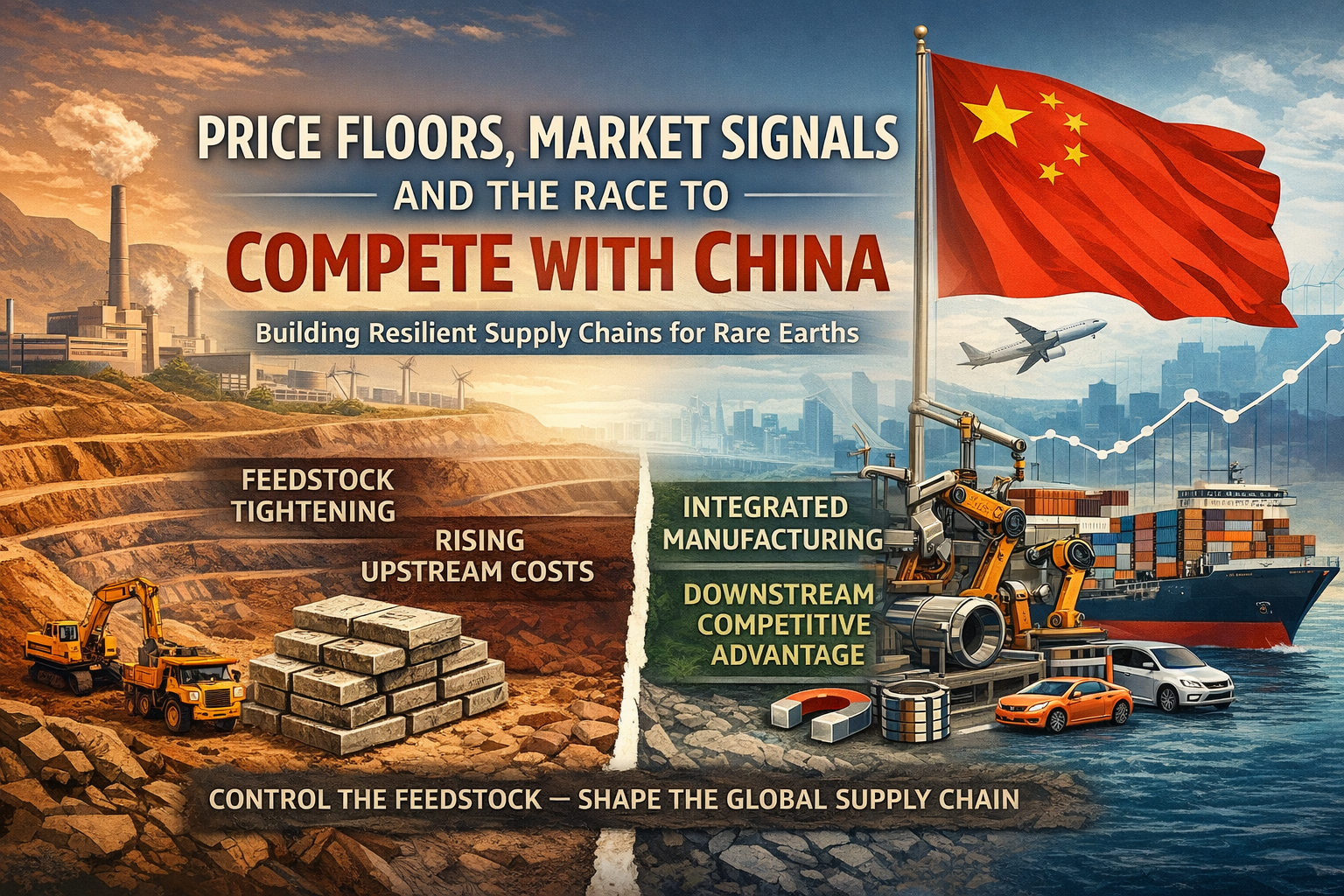

For years, rare-earth markets appeared to function around Chinese benchmark prices. Production concentration inside China, declining liquidity elsewhere, and the migration of transactions into opaque contract channels had steadily eroded external price discovery. When structured pricing arrangements emerged in mid-2025 — most visibly through MP Materials and the United States Department of Defence — they did not cause the breakdown; they revealed it. Capital markets were left without credible benchmarks on which to finance new non-Chinese supply. A paper circulated in July 2025 reframed the problem as one of market structure rather than price levels, arguing that restoring liquidity, demand anchoring, and continuous transaction flow was essential to rebuilding price formation outside China. This paper traces how that market-reconstruction logic has since moved from analysis to policy, culminating in Project Vault — structured through the Export-Import Bank of the United States — which targets market infrastructure rather than price support. Rather than raising prices, the new framework rebuilds the market itself

Why stabilisation emerged, why it is evolving, and what true supply-chain competitiveness requires

The debate around rare earth price floors is often framed as a choice between market forces and intervention. Price stabilisation emerged after a period of severe market dysfunction, when pricing collapsed below production costs across the industry and threatened the survival of non-Chinese supply chains altogether. Since then, prices have rebounded sharply, but the legacy of that collapse continues to shape capital behaviour and policy thinking. Support mechanisms that once served to stabilise a broken market are now increasingly being reassessed as attention shifts toward building supply chains capable of competing directly with China on cost, scale and reliability. This paper examines why price floors are justified when markets are distorted, why their role is evolving as economics and geopolitics change, and why long-term supply-chain independence will ultimately depend on competitiveness and volume adoption rather than permanent pricing protection.

This paper offers an interpretation of Mark Carney’s Davos 2026 speech, which framed the current moment as a rupture rather than a transition in the global economic and geopolitical landscape.

Using the speech as a point of reference, it examines how changes in incentives, constraints, and risk have altered the behaviour of states and markets — particularly as tools once associated with efficiency, such as tariffs, supply chains, and trade access, are increasingly used as instruments of leverage.

The focus is analytical rather than prescriptive, exploring why language rooted in an earlier phase of global integration now struggles to describe how the system is experienced in practice, and why recognising that gap matters for credibility, resilience, and cooperation.

Reflecting on the difference between using tools to explore ideas and presenting arguments as if they are settled. Tools can assist thinking and improve clarity, but responsibility for what is published — and its consequences — remains with the author.

The global rare earth market has already failed in its most basic economic function: it no longer converts scarcity into investable supply. Prices exist; demand exists yet supply outside China has not responded. The market has delivered exactly the outcome implied by its inputs.

This is why rare earths can be priced but not investable.

This failure is not new. What is new is that both sides of the market have now accepted it.

China has concluded that the pricing and export model that once supported both global supply and domestic industrial expansion no longer serves its strategic objectives. Export availability is now conditional, domestic value capture is prioritised, and Chinese prices no longer clear a global market.

At the same time, the rest of the world has recognised that rhetoric, strategy papers, and price observation do not create supply. Markets are outcomes, not instruments. When outcomes fail, the inputs must change. Duration, risk allocation, access certainty, and contract-backed pricing are now being deliberately engineered to produce a different outcome.

The market itself is unchanged. The conditions under which it operates are not.

Abundance is not supply.

“Rare earths aren’t rare” is a line we’ve all read countless times. It’s also where the story usually goes wrong. This short article explains why geology is the easy part — and why processing, scale, and control matter far more.

For much of the past decade, rare earth prices have remained largely disconnected from underlying demand growth. This outcome was not the result of weak end-use fundamentals, but of sustained supply expansion that absorbed incremental demand and suppressed price signals. Drawing on historical quota and pricing data, this paper shows how supply growth dominated price formation between 2015 and 2024, including the sharp price correction in 2023 driven by an additional quota issuance and a temporary slowdown in demand growth.

The paper then examines the implications of a market in which supply growth becomes more constrained, whether by policy, economics, or project lead times. It argues that as supply elasticity diminishes, prices are increasingly set at the margin rather than by average demand growth. In such conditions, even moderate demand growth can produce materially higher clearing prices, not because of absolute scarcity, but because prices must rise to induce new capacity. These dynamics have important implications for investment, policy, and the development of supply chains outside China.

Nigeria has already absorbed the political and economic pain of long-avoided macroeconomic reform. Exchange-rate unification, subsidy removal, and fiscal adjustment have restored a measure of coherence to the economy, but these steps alone cannot determine the country’s trajectory. The central risk now is not reform failure, but reversal.

This paper argues that once a population has endured the costs of adjustment, continuity ceases to be optional. The binding constraint on Nigeria’s long-term growth is no longer price distortion or capital scarcity, but a deep and widening skills deficit driven by the erosion of educational credibility. Without reinvestment in education and primary healthcare, the gains from reform will dissipate rather than compound.

Nigeria’s future is no longer pre-ordained. Whether recent sacrifices translate into sustained growth or are squandered through policy reversal will depend on consistency, institutional repair, and the intelligent redeployment of reform dividends into productivity-enhancing public goods.